In September 2015, the UN General Assembly released the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This contained 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), intended to make progress on globally important issues by the year 2030. These goals have been broken down into 169 targets and 232 indicators.1

These goals designed to replace the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were intended to be achieved by 2015. The SDGs were developed partly in response to lessons learned from the MDGs. The MDGs were perceived to lack ownership by all countries and appeared to be more relevant to global issues rather than some local country contexts. They appeared to be structured around the needs of donors as opposed to local development processes.2

The transition from the MDGs to the SDGs in Myanmar

As with other Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Myanmar faced difficulties in meeting the MDG targets. Challenges were faced with distributing the benefits of development to address the needs of vulnerable people within the country, as well as trying to implement a top-down process without the required resources to meet the targets.3

In 2011, the Union Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development developed the Framework of Economic and Social Reforms (FESR).4 This framework was designed to accelerate the achievement of the MDGs in line the National Comprehensive Development Plan (NCDP) 2011-2031. The NCDP is a development strategy that in the long-term is aimed at meeting the SDGs Targets and Indicators in Myanmar. The FESR was used as a bridge or a plan just for the first 5-years of the larger 20-year strategy to make national policies more focused on the SDGs across each sector or Ministyr and region in Myanmar. 5

However, at the start of 2015, while Myanmar was on track to meet some MDG targets (gender equality in school enrolment and access to clean water), the country would not completely meet any of the MDGs.6 A snapshot in late 2015 indicated only low to moderate levels of improvement for most MDG targets. 7 A lack of reliable data for measuring what progress had occured, such as information about poverty was identified as a problem that made it more difficult to address all the MDGs and move forward to planning the 2030 Agenda and achieving the SDGs.8

Some the other challenges experienced in Myanmar related to poverty included rapid growth of cities as people moved from rural areas as approaches to implement sustainable development and reduce poverty outside of the cities were not effective.

The FESR identified that decentralised planning processes would be required to encourage local leadership and ownership of development plans to reduce the gaps between rich and poor that were causing these problems. 9 These planning processes were intended to involve local levels of government to help understand which policies were making it more difficult to transfer benefits to poor or vulnerable people in Myanmar and how they might be changed. It was also thought they would provide some confidence for donors and international partners that their support would help to reform these problems.

Source: Wikimedia Commons – Clay Gilliland – Maymyo also known as Pyin Oo Lwin, Myanmar. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Localisation of the SDGs

Because of the problems with a lack of data make it harder to monitor the MDGs, it was very important to obtain a baseline for each SDG indicator to make sure the SDGs were a good fit for the situation in Myanmar. However, to establish a baseline, some challenges in the country needed to be considered properly.

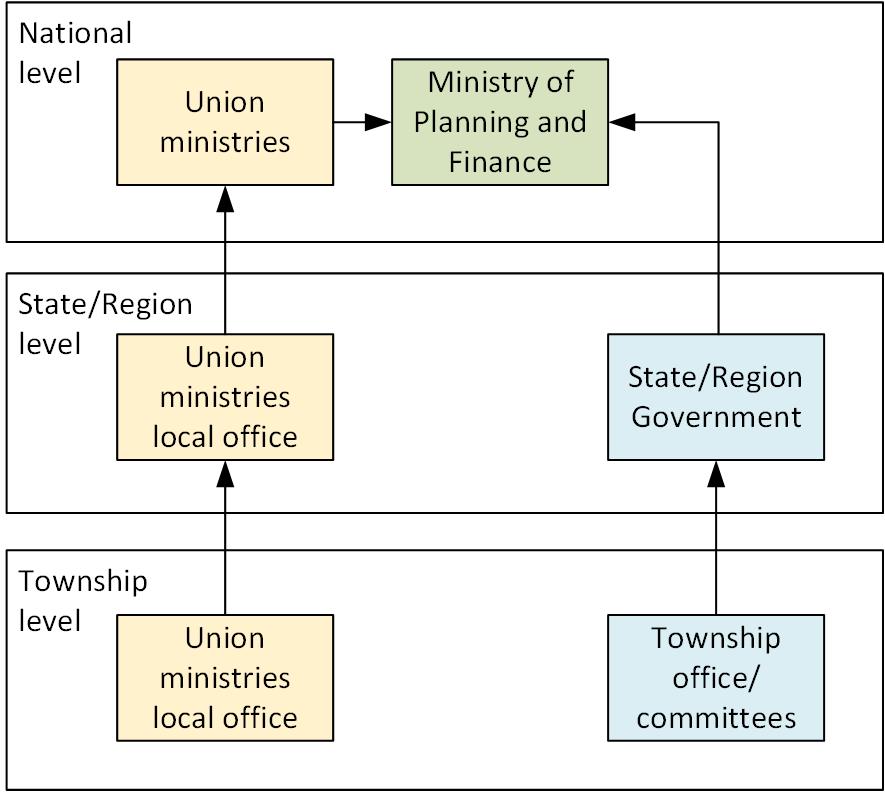

- Although the reform of local government institutions began in Myanmar in 2011, the implementation of the SDGs is still controlled by highly centralised decisions. Union level ministries in Myanmar still have strong control over political appointments and sources of revenue to implement the goals. The decisions made by national authorities and their State and Regional offices often do not consider the needs of local Development Affairs Offices (DAO). 10 As the DAOs do not have control over many decisions it affects their accountability and means that resources are not allocated to where and when they are needed. For example, in many cases, the DAOs at the township level do not have the permissiont to hire or reward their own staff or plan their own budgets. 11

- The awareness and understanding about the SDGs is limited in Myanmar particularly by the DAOs at the township level. These DAOs often have complex situations to be able to function properly, let alone implement the requirements to meet the SDGs. They also receive directions from several different sub-national offices of government Ministries and if these outcomes are to be met local officials need to be actively engaged in decision making and properly resourced. 12 However, at the township level, many political representatives are new to politics and have very little experience in government. Developing their capacity will require both time and significant effort.13

Monitoring and Reporting Framework in Myanmar. Source: Asia Foundation (2015) 14

When the SDGs are localised, these limitations need to be considered. Strong leadership will be needed to reform governance structures and ensure the rule of law is applied at all levels. This is necessary if activities at township level are going to help result in the acheivement of national policies, such as the NCDP (2011-2031). These documents outline how the SDGs will be implemented in Myanmar and cooperation is important.15

‘Means of Implementation’ for the SDGs

Myanmar is still classified as a ‘least developed country’ (LDC) and this has an influence on the types of resources the country is able to access to promote the SDGs. The country aims to graduate from ‘least developed country’ status by 2025.16 Myanmar has increased its GNI per capita to just above the target for graduation in 2018. This means that for the first time it has reached the level required to graduate for all three categories. The other two criteria are a Human Assets Index and an Economic Vulnerability Index.17

If these results can be maintained, Myanmar will graduate by 2025 and have access to more independent sources of finance, which will improve financial, human, and technological capacity of the Myanmar government to implement the SDGs.

Myanmar, as a country will need to use its resources more effectively, as well as securing external funds from development partners to focus on addressing some of the systematic problems affecting its ability to implement the SDGs. These problems include: gaps between national policies such as the FESR and how local institutions operate; encouraging different government departments and other stakeholders to collaborate to meet SDG targets; and improving the quality of data available in Myanmar to better track SDG indicators and improve accountability at all levels. 18

The inclusion of ‘means of implementation’ targets and indicators for the SDGs is in response to lessons learned from the implementation of the MDGs. Without this, Myanmar, as a LDC, would most likely experience the same financial and capacity constraints as when the country attempted to plan and implement the MDGs.

Global means of implementation

In 2016, Myanmar received US$1.53 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA). Although Myanmar still receives one of the highest levels of ODA in the region, the proportion of ODA as government income is decreasing. Non-ODA flows such as remittances and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) are growing at a faster rate and becoming more significant for achieving the SDGs. The increasing amount of FDI is providing incentives for the Myanmar Government to develop more transparency to give the private sector the confidence to invest in the sustainable development of the country.19

Source: World Bank and the International Monetary Fund20 21

National means of implementation

Government revenue from taxation and State Economic Enterprises (SEEs) is the largest sources of income for Myanmar to implement the SDGs.

However, while there was an increase in tax revenue to 10% of GDP for 2018, this is still below the average for other ASEAN countries (14% of GDP). Myanmar is also facing major challenges in increasing government revenue from SEEs due to corrupt practices. The profits diverted from these enterprises away from government revenue is higher than for most other developing countries. Reforms to prevent this situation are very important if the Myanmar government is going to have enough resources to implement the SDGs. The structure of many SEEs in Myanmar is complex, with low transparency and often only limited financial data is released publicly. Changes to the governance of SEEs in the mining and forestry sectors are particularly important.22

Monitoring and Evaluation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda

In 2016, a National SDG Steering Committee was established. The Central Statistical Organization (CSO) and the National Statistics Office serve as a focal point on this committee, which has the job of monitoring the SDGs. Their role is to work with all government departments to access to good quality data, which is disaggregated to understand how different groups such women and men, rich and poor, and urban and rural citizens are benefiting from sustainable development.

The steering committee has formed Committees for Data Accuracy and the Quality of Statistics (DAQS) at the national level, as well as for each state and region in Myanmar to support the collection of data that informs the goverment of the process toward each SDG target. It is intended that this data will enable the government to allocate resources for meeting the SDGs more transparently and directed to areas of most need.23

In 2016, an assessment of how ready Myanmar was to monitor the SDGs was conducted. 241 different SDG indicators were assessed to see whether they could be monitored by existing local institutions or whether they should be ‘split’ to make it easier for the different groups to collect the data. In some cases the way the indicators were described needed to be changed to make this easier in Myanmar and in other situations a different method would be needed to calculate the results specific to Myanmar.24

This assessment enabled the Ministry of Planning and Finance to understand what they needed to do to get ready for the SDGs. The Central Statistics Organisation was then able to change the data collection methods as needed for each SDG Indicator and teach people at State and Regional levels how to monitor the SDGs by holding workshops. 25 As a result the Myanmar government now has a joint data assessment with the UNDP and has developed an SDG Indicator Baseline Report (2017).26

This report shows that more work is still needed but most (75%) of the indicators will be able to be monitored by Myanmar, with only a small number needing to access data from international agencies. When the report was released in August 2017, the original 241 indicators has been split into 320. Of these, 61% were already available in Myanmar. The CSO in Myanmar has shown it has the capacity to collect most of the data required to monitor progress toward the SDG targets.

Source: UNDP in Myanmar (2017)27

They have developed the National Strategy for Development of Statistics (NSDS) to help with this.28 The CSO regrouped the split SDG indicators into different clusters that fit better with the structure of the Myanmar government.29 This has made it easier for different ministries to monitor the outcomes together in thematic areas, rather than for just for their ministry. Some of the thematic areas that different ministries have used to make joint recommendations include: child related SDGs;30 SDGs for vulnerable groups; gender related SDGs;31 private sector development;32 and environmental statistics for the SDGs.33

References

- 1. United Nations 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda For Sustainable Development”. Accessed March 2018.

- 2. UN System Task Team 2012. “Review of the contributions of the MDG Agenda to foster development: lessons for the post-2015 UN Development Agenda” Accessed March 2018.

- 3. The Hunger Project 2014. ”MDGs to SDGs: Top 10 Differences” Accessed March 2018.

- 4. Mekong Development Research Institute-Centre for Economic and Social Development (MDRI-CESD) 2013. “Framework for Economic and Social Reforms Policy Priorities for 2012-15 towards the Long-Term Goals of the National Comprehensive Development Plan” Accessed March 2018.

- 5. Asian Development Bank. 2014. “Myanmar Unlocking the Potential -Country Diagnostic Study.” Accessed March 2018.

- 6. Jolliffe, Kim (Myanmar Times). 2015. “Myanmar and the post-2015 development agenda.” Accessed March 2018.

- 7. UNSD. 2015. “MDG Country Progress Snapshot: Myanmar.” Accessed March 2018.

- 8. OECD. 2015. “Policy challenges in implementing development plans, Myanmar.” Accessed March 2018.

- 9. MDRI-CESD. 2014. “Myanmar’s Experiences with the Millennium Development Goals and Perspectives on the Post 2015 Agenda”. Accessed March 2018.

- 10. Asian Development Bank. 2014. “Myanmar Unlocking the Potential Country Diagnostic Study” Accessed March 2018.

- 11. Matthew, Arnord. Aung, Ye T. Kempel, Susanne. and Saw, Kyi P C. 2015. “Municipal Governance in Myanmar: An Overview of Development Affairs Organizations.” Accessed March 2018.

- 12. International Management Group. 2014. “Myanmar’s Experience with the Millenium Development Goals and Perspective on the Post-2015 Agenda.” Accessed March 2018.

- 13. Barker K. 2017. “Myanmar’s State and Region MPs Learning on the Job, and Online” Accessed March 2018.

- 14. Arnord, M. Y. Aung, T. Ye, S. Kempel, and K.P.C. Saw, 2015. “Municipal Governance in Myanmar: An Overview of Development Affairs Organizations.” Accessed March, 2018.

- 15. Ibid.

- 16. UNCTAD 2016. “The Least Developed Countries Report 2016 – The path the graduation and beyond: Making the most of the process”. Accessed March 2018.

- 17. United Nations 2018. “Least Development Country Category: Myanmar Profile – Data from the 2018 triennial review”. Accessed March 2018.

- 18. UNESCAP 2018. “Means of Implementation”. Accessed March 2018.

- 19. UNDP. 2016. “Overview Report of Development Finance in Myanmar.” Accessed March 2018.

- 20. World Bank 2017. “World Development Indicators”. Accessed March 2018.

- 21. International Monetary Fund 2017. “IMF Data”. Accessed March 2018.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. UNDP. 2016. “Readiness of Myanmar’s Official Statistics for the Sustainable Development Goals.” Accessed March 2018.

- 24. Ibid.

- 25. Asia-Europe Environment Forum 2017. “Sustainable Development Goals: Planning for Implementation, Workshop Report, Accessed March 2018.

- 26. UNDP in Myanmar 2017. “Measuring Myanmar’s Starting Point for the Sustainable Development Goals: SDG Baseline Indicator Report”. Accessed March 2018.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. UNDP. 2016. “Readiness of Myanmar’s Official Statistics for the Sustainable Development Goals.” Accessed March 2018.

- 29. Arnord, M. Y. Aung, T. Ye, S. Kempel, and K.P.C. Saw, 2015. “Municipal Governance in Myanmar: An Overview of Development Affairs Organizations.” Accessed March, 2018.

- 30. UNICEF 2016. “New Vision for Children in Myanmar: Using recent data to analyze the situation of children and what it means for Myanmar”. Accessed March 2018.

- 31. Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process 2017. “International Standards Guiding Gender Inclusion in Myanmar’s Peace Process”. Accessed March 2018.

- 32. UNOPS 2018. “Mobilising Myanmar’s Private Sector to Achieve the Sustainable Developement Goals”

- 33. Maung, W. 2017. “Prioritizing and Planning the Implementation of Recommendations to Support Country Actions”. Accessed March 2018.