Current State of Information Availability and Quality in Myanmar

Access to information is the fundamental right of freedom of expression as recognized by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Article 19 states that the fundamental right of freedom of expression encompasses the freedom to “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. Myanmar […]

Access to information is the fundamental right of freedom of expression as recognized by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Article 19 states that the fundamental right of freedom of expression encompasses the freedom to “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”.1 Myanmar is one of the countries that fail to include Right to Information as a fundamental right in its constitution.2

The Freedom to access and express information accessibility began to improve following the country opening up to the world in 2012. However, Myanmar is now one of the least connected countries in the world regarding access to information and data. There is limited access to the internet, making digital information difficult to access, and a lack of adequate digital infrastructure affecting access to reliable and up-to-date information. After deposing the elected government on February 1, Myanmar’s military attempted to seize control over information and data availability. This has made it far more difficult for people to access online information that may be a matter of life and death.

Data availability and quality

Before the military ruling in 2021, data quality and availability were limited. However, During the civilian government, Myanmar has taken some important steps to strengthen the right to access information in the country. The Central Statistical Organization (CSO) is a government agency that leads data governance in Myanmar. It is also a leading member of the Central Committee Data Accuracy and Quality of Statistics Committee, which plays a coordinating role in the development of the National Statistical System. 3

Following February 1, 2021, the State Administrative Council (SAC) has imposed increasing restrictions on internet access, and information which civilians face greater information availability and quality scarcity. Furthermore, many news media outlets, television channels and independent ethnic websites4 have been banned. That has made it extremely difficult for people to access, upload and share online information and data, affecting data availability and quality.

While the quantity, quality, and variety of data and information have been improving worldwide, Myanmar has steadily declined since 2020. According to Open Data Watch, Myanmar Open Data was ranked 87th out of 187th before the coup and 95th out of 193th globally after a year’s coup.5 Overall, Myanmar’s data openness declined based on its overall score from 51 in 2020 to 50 in 2022, (as shown in Graph 1). The scores are scaled from 1 out to 100. The information below shows the overall score, which is a combination of a data coverage sub-score and openness sub-score, includes assessments of the country’s statistical capacity, links to relevant laws, and comparative measures of the country’s performance on other measures of data coverage, openness, and government transparency. Nevertheless, the Global Data Barometer report 2022 showed no data about data availability and quality in Myanmar 6 which infers that data and information availability and quality are limited.

Access to up-to-date information

During the political and pandemic crises, accessing up-to-date digital information and reliable sources can be a matter of life and death. Online information, including MOHS 7, MIMU8, Open Development Myanmar9, and UN10, launched up-to-date COVID-19 information platforms to strengthen the lives of people in Myanmar. These platforms are seen as trusted sources of information consumption. However, Myanmar authorities are taking advantage of the pandemic by persecuting independent sites, journalists, attempting to shut down media sites, and further restricting public access affecting up-to-date information availability.

The civilians, particularly in the non-state control area, face greater information inaccessibility in order to make informed decisions for themselves and their families. The people in the conflict zones do not usually receive needed and timely information from mainstream media outlets, including RFA Burmese, DVB, Mizzama, and Khit Thit Media, which are seen as trustworthy by most people in Myanmar.11 Local media and social media, especially Facebook, become the primary source of up-to-date information for people in conflict and rural areas.

The absence of accurate and reliable information

Accessing inaccurate and misinformation is worse than not having access to the data and information. During the Coronavirus pandemic, internet users increased.12 Accessing and sharing information online – including necessary healthcare information 13– became more important, especially since pandemic measures like lockdowns and social distancing14 made it difficult to meet in person. However, a generally low sense of trust in data producers15, plus limited reliable information due in part to disrupted internet access, has added to a breakdown of the healthcare system.16 During the pandemic in 2021, data that were taken by the military regime on the COVID-19 cases in-country, there is no accurate sense of the pandemic in Myanmar.17

The pandemic drew attention to data reliability. After the start of the pandemic, Myanmar’s Ministry of Health and Sports (MOHS) began disseminating information about COVID-19, including the latest data, on its online platform.18 In many cases, the government used the pandemic to restrict access to information and data across the region. However, since the military took over in February 2021, there have been questions about whether the data of deaths due to COVID-19 have been undercounted in the country, as the Tatmadaw or SAC does not count home deaths.19 For instance, there are also no numbers on infections of Muslims living in camps. 20

Ethnic minorities have also been the subject of COVID-19 misinformation.21 There are reports of disinformation created by fake Facebook accounts specifically targeting Rohingya.22 Muslim communities, especially in remote areas, are doubly impacted by misinformation (e.g. around cures for the virus) as they have little access to information to dispel myths. For instance, villagers living in KNU-controlled and some mixed-control areas in Southeast Myanmar have limited awareness about COVID-19 outbreaks.23 Another issue is that even if information is available, the MOHS information about the pandemic is only in Burmese. This adds an additional layer of difficulty for ethnic people, who have a limited capacity to read and understand the Burmese language. Further, with fewer digital literacy tools to analyze the information, ethnic minorities are at greater risk of misinterpreting the mis/disinformation.

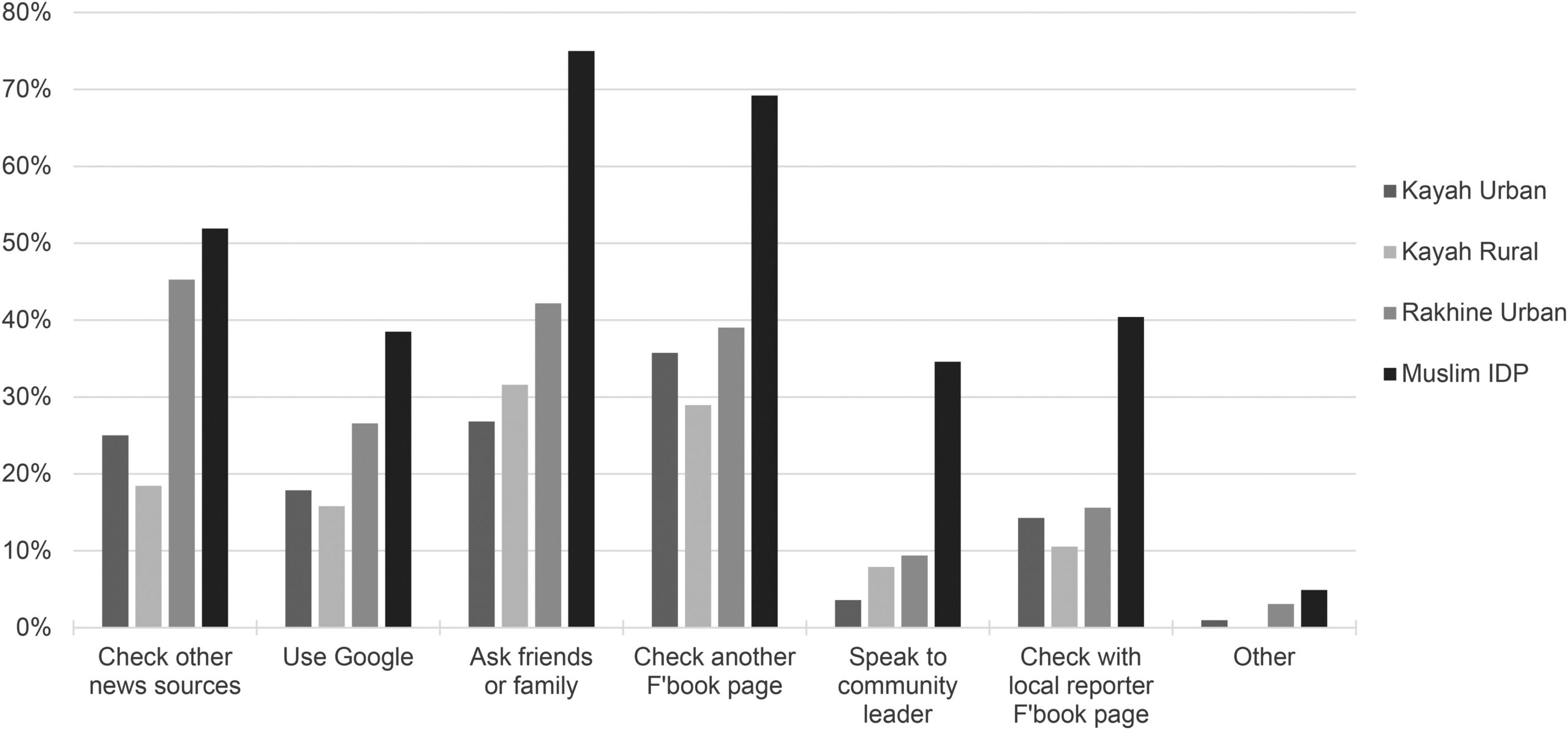

Poor access to information also impacts external knowledge about communities in Myanmar, thereby contributing to the spread of misinformation. For example, minorities and marginalized groups are often singled out for poor digital literacy, and blamed for creating and spreading disinformation and hate speech. In contrast, a survey from Kayan and Rakhine State shows that rural youth from Kayan want to assess the accuracy of information, using various sources to do so.24 The below (graph 2) shows how ethnic youth use Facebook as a primary tool to pursue information and ask questions among their communities.

Graph 2: Checking accuracy of news on social media. Graphed by Brad Ridout et al. via Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Licensed under CC BY-NC.

Prior to 2020, in terms of trusting news on Social Media, predominantly Facebook, the study from Social Media Use by Young People Living in Conflict Areas, found that IDP respondents had a significantly higher level of trust in news on social media compared with the urban and rural respondents. The youth respond that they be less trusting of News Media as they have more experience on Social Media. On the other hand, users who are new to social media, are most likely to believe fake news. In order to check the accuracy of the information, asking friends and checking another Facebook page are the majority of source accuracy checking.

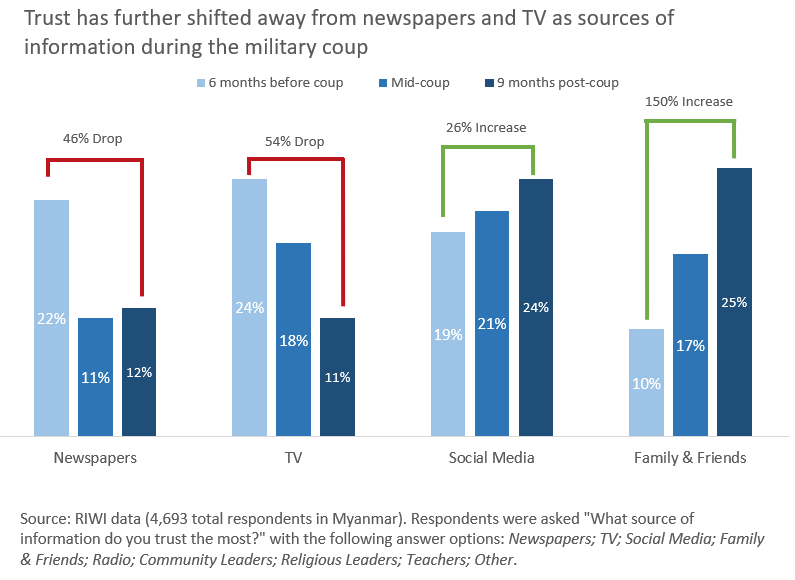

The Frontier study showed that most consumers believe state-owned newspapers and broadcasters provide the most trustworthy and reliable news and information prior to the coup.25 Following the SAC’s ruling, civilians mistrust any news, newspapers and TVs associations with military-controlled media outlets including, MRTV, MWD and A Lin Tan media outlets. Just like the traditional information sources like TV and newspapers further declined.26 Instead, RIWI data also stated that social media and family and friends remained the most trusted sources.27 (see Graph 3)

Graph 3: The most trusted source of information. Graphed by Gayatri Malhotra. Via RIWI. Licensed under: Unsplash.

The current state of information availability and quality in Myanmar is challenging due to various factors, including political instability, limited technological infrastructure, and ongoing conflicts in some parts of the country. As a result, policymakers and humanitarian organizations face challenges in accessing accurate and reliable data to inform their decision-making. In addition, people from certain areas, especially in conflict zones or areas controlled by non-state actors, face a greater significant challenge to access online information affecting a matter of life and death.

Furthermore, the quality and reliability of the available information in Myanmar can also be a concern. In a society where misinformation and the spread of false information pose significant challenges, ensuring the accuracy and trustworthiness of the information is crucial. The rise of social media and the ease with which anyone can create and share content means that there is a greater need for media literacy and critical thinking skills.

References

- 1. UNESCO. (n.d.). Access to Information Laws. Accessed October, 2023.

- 2. Article 19. 2019. Report: The right to information and natural resources in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 3. The Asia Foundation. 2020. Developing Myanmar’s Local Data Ecosystem. Accessed October, 2023.

- 4. Kelly Koh, et al. 2022. Myanmar: The State of Internet Censorship 2022. Accessed October, 2023.

- 5. ODIN. Country profile: Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 6. Tim Davies & Silvana Fumega. 2022. Global Data Barometer (2022). Accessed October, 2023.

- 7. MOHs. Ministry of Health and Sports. Accessed October, 2023.

- 8. MIMU. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Accessed October, 2023.

- 9. Open Development Myanmar. 2020. Essential Information on COVID-19 in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 10. WHO. 2022. Promoting local preparedness capacities and access to COVID-19 information through Open WHO Myanmar channel & Viber community. Accessed October, 2023.

- 11. Emilie Lehmann-Jacobsen, & Myat The Thitsar. 2022. “News is life and death to us” – Understanding media audiences in post-coup Myanmar” in International Media Support 5. Accessed October, 2023.

- 12. Freedom House & Freedom Expression Myanmar. 2021. Freedom of net in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 13. Vandana Sharma et al. 2021. COVID-19 and a coup: blockage of internet and social media access further exacerbate gender-based violence risks for women in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 14. MOHs. 2021. The list of the township declared to stay home. Accessed October, 2023.

- 15. Radio Free Asia. 2021. Myanmar Citizens Reject Junta’s Immunization Plans and Chinese COVID-19 Vaccines. Accessed October, 2023.

- 16. The Irrawaddy. 2021. Myanmar’s Third Wave COVID-19 Deaths Now Exceed Fatalities in First and Second Waves. Accessed October, 2023.

- 17. Vandana Sharma. 2021. COVID-19 and a coup. Accessed October, 2021.

- 18. Nan Lwin. 2020. Combating Fake News in the Time of Coronavirus in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2021. Accessed October, 2023.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Reuters. 2021. Myanmar COVID vaccination rollout leaves Rohingya waiting. Accessed October, 2023.

- 21. Article 19. 2020. Freedom of Expression concerns related to Myanmar’s Covid-19 response. Accessed October, 2023.

- 22. Annie Gowen & Max Bearak. 2017. Fake News on Facebook Fans the flames of hate against the Rohingya in Burma. Accessed October, 2023.

- 23. KHRG. 2021. Left Behind: Ethnic Minorities and COVID-19 Response in Rural Southeast Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 24. Brad Ridout et al. 2020. Social Media Use by Young People Living in Conflict-Affected Regions of Myanmar. Accessed October, 2023.

- 25. Frontier. 2018. State-owned media the most trusted, study finds. Accessed October, 2023.

- 26. Catherine Barker, Mercedes Fogarassy, and Shaelyn Laurie. 2021. Trustworthy information sources in Myanmar: What do people trust now?. Accessed October, 2023.

- 27. ibid.